Every week, we'll be sitting down with one of our gallery artists to discuss their work, process, inspiration, and stories. This week we're speaking with Susan Cantrick.

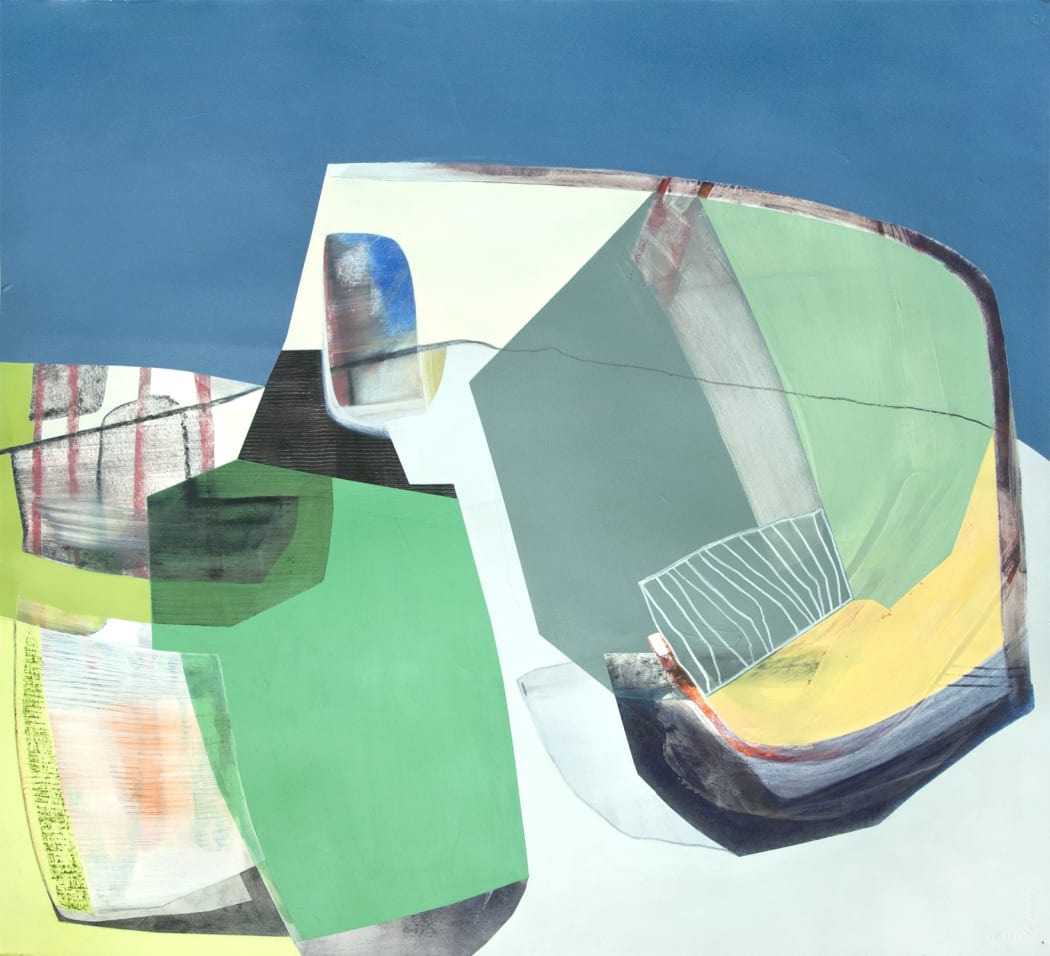

"SBC177"

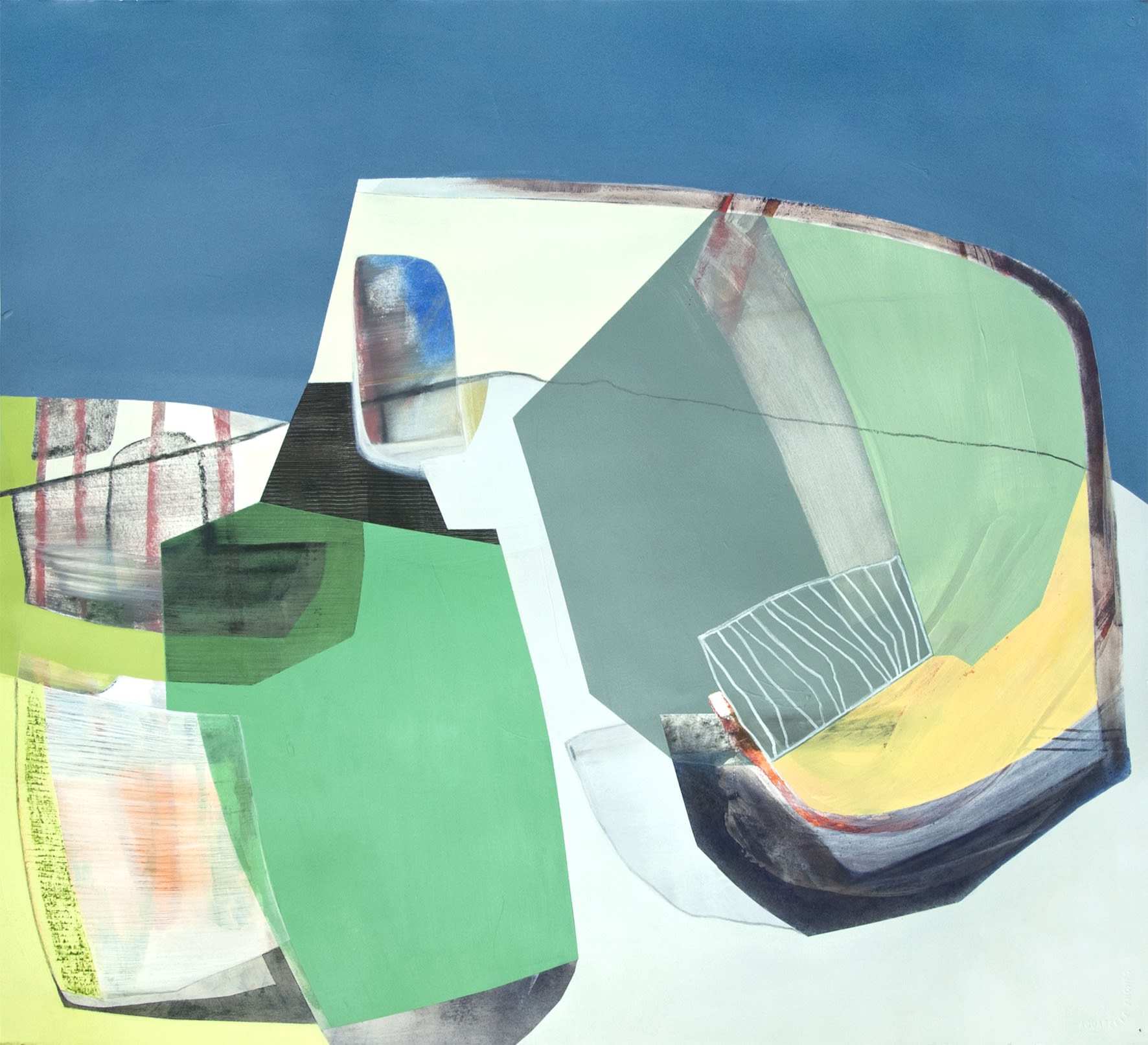

Susan Cantrick's work is at the threshold of when sensation, emotion, memory, and intuition transform into cognition, capturing the moment at which the image begins to filter coherently into consciousness. She revels in the process of painting for painting's sake, a tool used for perceptual inquiry rather than representation. Sometimes experimenting with digital techniques to build up layers, Cantrick reworks and resolves the remnants of previous paintings to create something new, each piece rich with history. She spoke with us from her studio in Paris about how she developed this process, the benefits of her indirect path to becoming a visual artist, and the psychological exploration behind her work.

What are your earliest memories relating to art?

When I was in kindergarten, we made a big papier mâché giraffe. I loved doing that, and the memory of that experience has remained vivid. It was obviously an awakening to how much I love making things, a trait that I must have inherited from my mother. She had innate artistic talent, taught me the basics of drawing, and helped me with many of my grade school art projects. Thanks to her, I won a few prizes. But my fondest memory of working with her is one of making a Christmas tapestry together, of a partridge in a pear tree. We sewed felt shapes onto a burlap background. She had interesting, unconventional notions about recycling shapes that were left over from previous projects, as well as the brilliant idea (or so I thought at the time) of turning one pear upside down. She eventually became an assistant librarian at the Albright Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo, where I worked for a while part-time during my college years. Every day, thanks to their strong abstract expressionist collection, I walked past Gorky, de Kooning, Pollack, Still, and Frankenthaler. My mother was a fan of these painters, so her influence rubbed off in that way as well. My father's indirect influence cannot be ignored, though. He was a musician and composer whose musical and intellectual leanings were avant-garde. Strange flute sounds were always in the air. What with two such creative parents, I grew up quite acclimated to experimental artistic values.

How and when did you start becoming an artist yourself?

Though my first career was in music, I always felt that visual art was my missed métier. But it wasn't until quite late - in my mid-forties - that I made the lateral move to art, after deciding to retire early from music because of chronic tendinitis. But even then, I didn't quit performing thinking that I'd become a painter. I was going to go back to teaching violin, but couldn't find the right conditions in Paris for doing that, so I decided to take a drawing course. The teacher was great. Within the first semester she had us doing large-scale drawings of tiny objects (one of many tactics she had for getting her students to see objects unconventionally.) I became immediately hooked and signed up for more courses, some of which took me to draw at the Louvre and other museums, at cafés, and in other public venues. I fortunately encountered only good teachers, all of whom were talented, well-trained artists and great enablers. For five years I did nothing but draw, paint, and take photographs in class settings, before finally settling into a studio on my own.

Photo courtesy of the artist

What was the evolution like for finding your voice?

From the beginning, even while still attending classes where I was drawing and painting from life, I'd go home and do abstract watercolors. So even though I loved drawing from life sources, I knew that ultimately what I wanted to make was abstract paintings that had no direct link to the real world. The drawing was extraordinarily satisfying and of course essential for internalizing my real-life observations and learning how to transpose them onto a two-dimensional surface, but the time eventually came when I felt compelled to move away from it. With basic training behind me and ideas percolating, finding my way with them was just a matter of putting in the hours. My musical training served me well both in terms of discipline already ingrained but also in helping me understand the ups and downs of the creative process -- how important it is just to keep going, without succumbing to the demons of doubt and judgment.

Of course, because I wasn't in an institutional setting, I had to compensate as best I could for not being taught contemporary theory and techniques, but I'm a pretty good auto-didact and was interested in that stuff anyway, so it was and continues to be just a part of my personal research.

What is your process like? Could you elaborate on how you work with digital techniques?

For the past six or seven years, I've been painting from digital studies that are composed (in Photoshop) of fragments of my previous paintings. The results resemble a gamut of genealogies or a slice of the earth's geological layering. The digital studies are, as far as I'm concerned, analogous to traditional, non-digital studies. The computer, in other words, is just another instrument in the toolkit - just another means to the end of painting, which has its own unique life. Sometimes, to loosen up a bit, I start a painting without any study at all, digital or otherwise. Perhaps one day I'll abandon digital means altogether, but for now they're working well for me.

I use Photoshop - as do many artists today -- because I can do things with it that I couldn't do with more conventional means, like superimposing translucent layers of imagery cropped from photos of my previous work, altering their color in ways that would never occur to me if I were working conventionally, cropping and altering the compositions in ways that I couldn't otherwise do. It enlarges the realm of possibility and surprise in unique ways. It also allows me to work with great freedom and speed - almost the speed at which I think. Once I start a painting, I can take a photo of it at any stage and rework it in Photoshop without analyzing or worrying about whether doing x, y, or z is going to ruin it. There's nothing foolproof or easy about this procedure, and in fact it can as easily open up new possibilities, raise new questions, and slow me down, as solve a problem. But I like problem solving and the tension it generates in the work itself, so for me, this added layer of complexity ups the ante in constructive ways.

Photo courtesy of the artist

I follow this procedure whether I'm working on canvas or paper. However, with small works on paper that can fit through my ink-jet printer, I might add a stage which involves embedding a digital print. That is, I'll start a paper painting, then print some imagery on top of it, and then paint on top of that. It's an interesting way to impose a translucent layer of specific imagery that will nevertheless inevitably print in unexpected ways on top of the painting, taking me in a new direction.

Necessity led me to Photoshop. Early on, when I was still working in watercolor and taking photographs, I was also doing a lot of conventional collages and making some artist's books. I wanted to make a book superimposing some photo imagery, but was not getting the results I wanted by printing my photos on translucent paper or doing photo transfers. By chance, I met someone who showed me how I could achieve the requisite translucent layering in Photoshop, and subsequently I acquired the software and learned how to use it.

What elements are most important to you in your work?

Clarity, complexity, and vitality. I see my paintings as analogs of my perceptual experience, which I identify as the pre-verbal threshold of cognition, where thought begins to cohere. But I want my paintings to be as articulate as possible, so balancing the three elements is a constant challenge.

How do you seek to portray that moment of perception? What interests you about that moment?

I can address those questions best by talking about painting itself. What interests me about painting -- besides its sensual aspects and the challenge of its flat "space" -- is that, despite being a non-verbal form of expression, it has, like music, the capacity to project great clarity (which is not the same thing as certitude). It fascinates me that humans have this capacity for sub-linguistic lucidity which, I think, is the essential impetus to the non-verbal arts.

Photo courtesy of the artist

In my written statements about my work -- on my web site, on your site, and elsewhere -- I've deliberately steered clear of talking about content and meaning in my work, focusing instead on impetus, or how I mentally situate myself as a painter, at the threshold of cognition. I don't think in terms of portraying the moment of perception so much as filtering it through the act of painting. I'm not trying to depict my perceptual experience; I'm materializing it. In other words, it's not that my work is "about" perception, it's that perception is its generator. For me, the paintings are a bit more like people than pictures in the sense of projecting a presence rather than a meaning. They are as much state of mind as process and as much process as object.

With so much work today being mediated by texts, I prefer to redirect attention to the non-verbal register, both in my work and in how I talk about it.

What are your other inspirations and influences?

All good painting, of course. It's as important to me to see what my contemporaries are doing (especially those who are concerned with just letting painting be itself), as to educate myself about what has been done in the past. And of course I tune into the enriching parallels between music, poetry, and painting. But I think that, more than anything, the physical world is an inevitable influence. I'm continually amazed at how body and landscape (both urban and natural) creep, unsolicited and sotto voce, into my paintings. Robert Hughes said it well: "Everywhere and at all times, there is a world to be re-formed by the darting subtlety and persistent slowness of the painter's eye. We are never loose from our bodies and the re-embodiment of our experience of that world - its delivery from the merely conceptual, the unfelt, the second-hand or the rhetorically transcendent - is what painting offers."

Did you find that your move to Paris affected your work in any way?

Yes, but probably not in the ways you might expect. Which is to say that Paris has influenced my trajectory as an artist more than the content of my work.

First of all, I'm not sure that I'd have quit music and become a painter had my husband and I stayed in Washington, D.C., where I was developing a teaching career. The move to Paris, ironically, put me in a position to do more performing and no teaching, which meant an aggravation of the tendinitis, which led to my early retirement.

Photo courtesy of the artist

Secondly, as a latecomer to painting, I was too old to enter the Écoles des Beaux Arts system here, so the conventional academic route was closed to me. That has been part blessing and part curse. I avoided all the awkwardness inherent in trying to become a painter in an atmosphere still dominated by conceptual art, while being deprived of a systematic education, not to mention the networking and prestige associated with being a graduate of an academic institution. I like to think that the blessing part is ultimately more significant than my lack of a diploma. For all the benefits of a formal education, there's also something to be said for being able to develop outside the academic box. Nevertheless, I'd certainly have pursued formal training had I been able to.

Of course, proximity to great museums like the Louvre, Orsay, and Pompidou in Paris, as well as all the other rich public and private collections here and in other nearby European cities like London, Amsterdam, and Berlin, continues to provide a great advantage for continuing education.

Where do you see your work going from here?

Not to be evasive, but who knows? As Picasso said: "If you know exactly what you are going to do, what is the point of doing it?" I'm not Picasso, but quite honestly, my ongoing goal is simply to make the most interesting paintings I can and to surprise myself in the process. Because of the way I work, my supply of digital studies always far exceeds my capacity to realize them all, which means that I'm continually challenged by the choice of which ones to paint next. Do I want to carry forward an idea from the latest painting(s) or do I want to double back and explore some previous ones, utilizing studies that have so far stood the test of time? Or proceed some other way? A mid-term goal is to challenge myself with a residency, probably in the U.S., and in the near term, I'd like to create some drawings based on previous paintings. But all I can say for the immediate future is that my next paintings will probably be in a large square format (120x120 cm), in anticipation of having a set from which to choose one for a group show coming up here in February 2017.

"SBC196"

Explore more of Susan Cantrick's work here.