Every week, we'll be sitting down with one of our gallery artists to discuss their work, process, inspiration, and stories. This week we're speaking with Jeri Eisenberg.

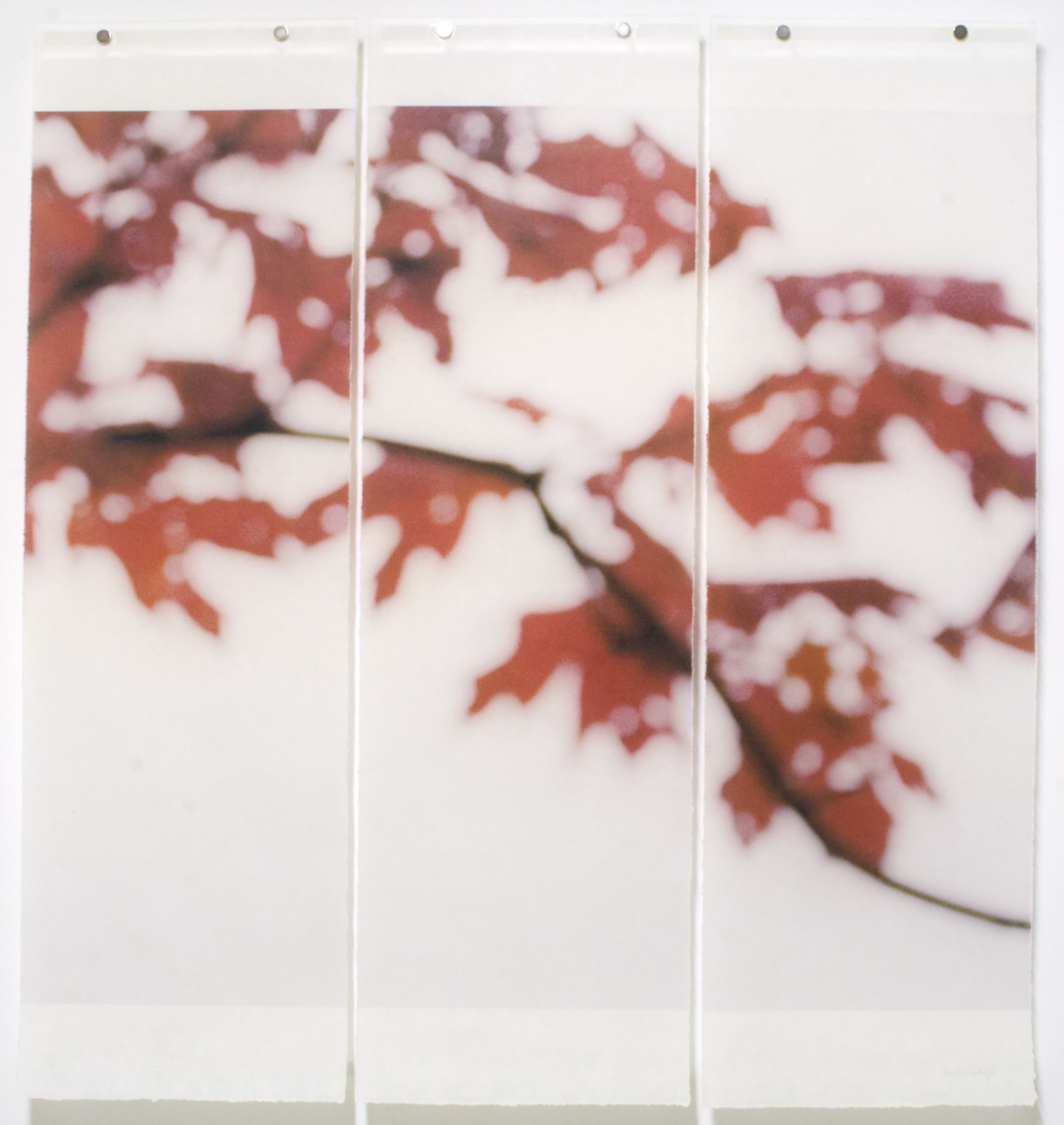

"Till It's Time to Go No. 3"

Inspired by watching the changing seasons in the woods surrounding her home, Jeri Eisenberg's "A Soujourn in Seasons" series seeks to capture the ephemeral nature of a landscape. Photographing small details of trees and plants on a large scale, she uses an oversized pinhole or radically defocused lens so that only the strongest elements of her subject remains. The photograph is printed onto Japanese Kozo paper and then painted with encaustic as the panels are pulled over a hot metal plate, allowing the wax to fully infuse the paper. This creates an inherent luminescence to the work, interplaying with Eisenberg's fascination with the movement of light. We spoke with her from her studio in Upstate New York about developing this process, the personal parallels to the direction her work has taken, and about being "an unrepentant aesthete."

What are your earliest memories related to art?

My dad made his living as a commercial artist in New York City advertising studios, and art was always around our house. I grew up with reproductions of Modigliani and Gauguin on the walls, and I often paged through my dad's art books, falling in love at a young age with Bonnard and Rouault. But high modernism was the central visual aesthetic that prevailed in my childhood home and that shaped my eye.

How did you start becoming an artist yourself?

When I was young, my dad and I took weekend ceramics classes together. Then during high school, I started working in the wet darkroom. I took a photo class or two during college, but that was the extent of my early art education. I headed directly to law school after graduating from college. It was the mid-seventies, and I thought I was going to help change the world. I practiced law for 15 years, advocating for alternative energy and conservation, before acknowledging that law was the wrong emotional fit for me. It's not a good place for a conflict-avoidant person. With my husband's encouragement, I quit and turned to something I knew would make me happy: photography. I took community college courses to reintroduce myself to the wet darkroom, started showing regionally, and ended up teaching as an adjunct at a local college. I ultimately went back for my MFA well into adulthood. Becoming an artist was not as much a conscious path for me as it was slowly finding the person that I am.

What draws you to nature as a subject?

Although I grew up in the metro New York City area, I've spent virtually all of my adult life to date in rural or exurban areas of upstate New York. For the last 30 years, I've lived on 18 acres of land in a home surrounded by third generation deciduous woods, not far from the Hudson River. Watching the trees, the grasses, and foliage change with the seasons has become an incredibly important component of my life. I love visiting other environments like the city or the desert, but leaving the comfort of woods around me for good would make me feel bereft. I get true pleasure from looking carefully at the natural world that surrounds me.

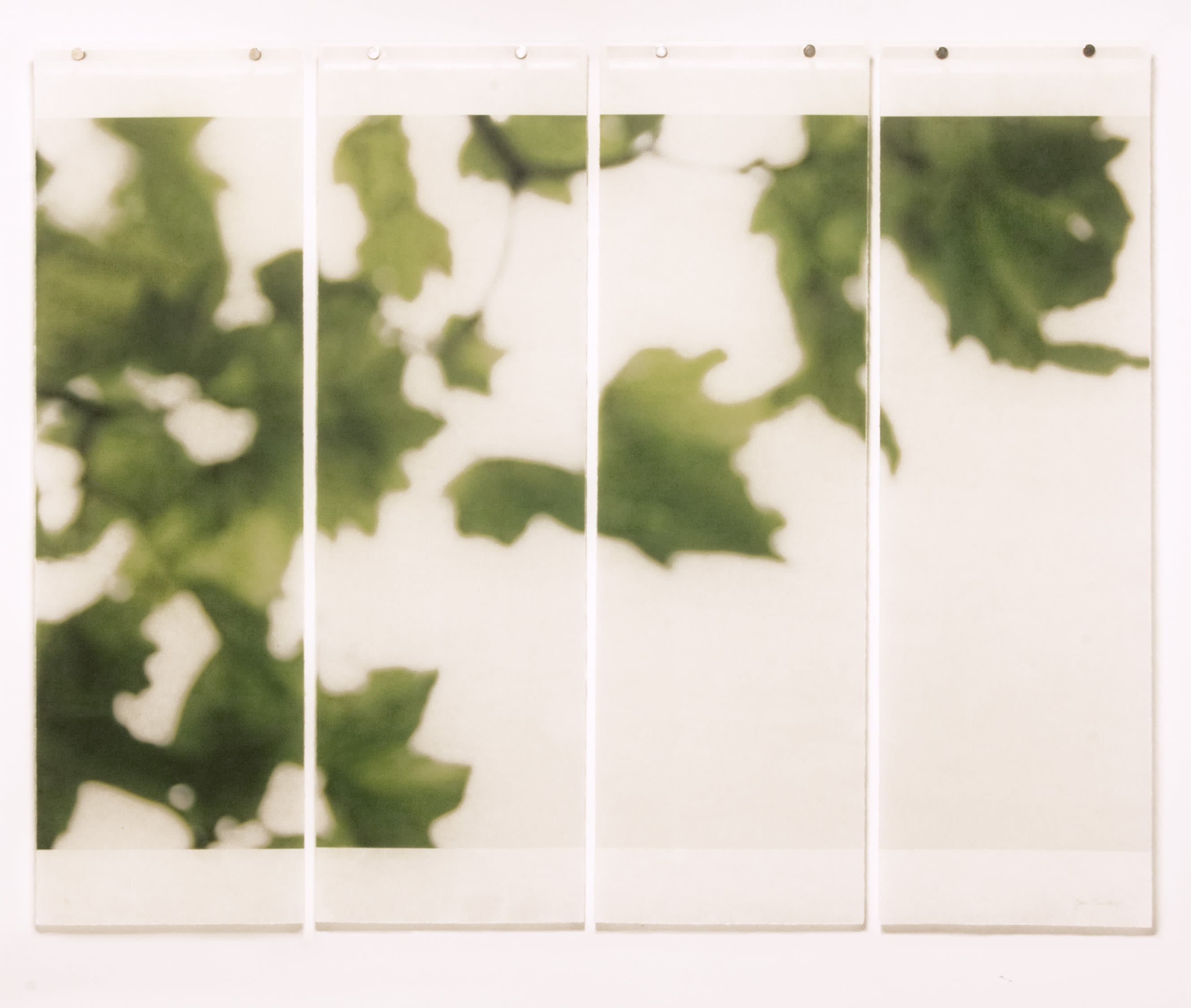

"Sugar maple Flutters (Red), No. 3"

How did you develop your process?

The process I use for my major series grew very organically. It started with an artist's grant I had to turn unused storefront spaces in Troy, NY into camera obscura. I planned to use mural paper on stands inside the spaces to capture street scenes. I needed to see where I wanted to set up the stands, and when I first let in some light to do so I used larger than appropriate apertures. It was the resulting out-of-focus dancing light abstracts formed by the city curbside trees that caught my heart. I ended up quickly completing the project I had gotten the grant for (using appropriately sized apertures to get focused images), and then went on to start the beginnings of my Sojourn in Seasons series.

I turned spaces in my home into camera obscura to capture unfocused abstractions of the woods surrounding my house on mural paper. I took small handmade pinhole cameras into the woods, or used my 35mm cameras with pinholes in the body caps instead of lenses. I moved on to color film and ultimately using a defocused lens as I started to shoot digitally. Along the way, I tried printing on a variety of substrates, fabrics, vellum, mylar and various fine art papers with and without wax, all in the attempt to capture that soft dancing light filtering through trees. I settled on waxed Kozo because it allowed a luminance to come from within the work and provided a very organic feel.

This evolution of the series to its current format was happening over a timeframe in which my father was losing both clarity in his sight due to mini strokes and his memory due to dementia. It became clear to me that the work I was producing was very close to what he then could perceive and hold on to: images that faded in and out of recognizable form. The series took on a greater meaning for me and became metaphorical. Lives as well as leaves blossom, swell, wither, and fall. The images purposefully straddle the line between the concrete and the abstract, the real and the remembered; they echo for me the ephemeral nature of all life.

"Live Oak"

You typically work in diptychs and triptychs, and have your pieces displayed so that they're floating a bit away from the wall. How does this add to what you're working toward with these pieces?

I first started working with multiple panels as a practical matter. Kozo paper was available only in sheets of a certain size (about the size of my diptychs). In order to get larger, I had to work in segments. Using multiple narrow panels allowed me to do this and also allowed me from the beginning to print my own work rather than using a commercial printer. That control was important to me. I was working in this format for about a year before I realized that the windows in my home are long and narrow, and in sets of twos, threes, or more. It's almost the same aspect ratio as my Kozo panels. So, I'm always looking out on my woods as diptychs, triptychs, and quads. I'm sure, in retrospect, that my subconscious was primed to work in this manner.

Using multiple panels is an important component of the work now. I like the additional abstraction that occurs when considering only a panel at a time. The slight movement in the panels when the bottoms are untethered pleases me because it echoes how foliage, blossoms and branches sway in the real world. Conceptually, the segmenting reinforces the notion that what we perceive is always only a piece of the whole. Beauty is fragile, fleeting, and fragmentary. You need to hold on to what you can.

Where do you see your work going from here?

I've started capturing movement more directly in my images of the treed landscape, and have been shooting different qualities of light in the skies and reflected on bodies of water. I'll see where these go, but clearly I'm still fascinated by qualities of luminance and dancing light.

I've also been experimenting with incorporating images into glass. It's been exciting to learn skills in a new medium that might complement my imagery.

I remain an unrepentant aesthete, and will continue to seek out and attempt to convey the bittersweet quality that beauty has, which can both tear at, and repair the tear, in a heart.

"On the Canopy Edge"

See more of Jeri Eisenberg's work here.

Comments

Jeri, you teach me so much about art and beauty. You articulate so well things that I see but don't now how to verbalize. Thank you..

As your mother I was fortunate to watch you blossom and grow. Your eye for beauty was always there and over the years you have increasingly been able to capture it and help all of us to share it with you.. We love you dearly.